Offshore wind in a big FLOW

Dutch research project shows costs offshore wind can be reduced 40% in ten years

by Rolf de Vos and Ernst van Zuijlen

June 16, 2016

A shorter version of this article was published at Energypost.eu

The Dutch research programme FLOW (Far and Large Offshore Wind energy) shows that a well-coordinated approach between industry, knowledge institutes and government can achieve 40% cost reduction in ten years in the offshore wind sector. In about ten to fifteen years, offshore wind should be able to manage without subsidies.

The FLOW book mentioned in the article is available as a free pdf:

- Download the FLOW book (English, PDF, 20MB)

- Download het FLOW boek (Nederlands, PDF, 20MB)

On 15 June the final results of the Dutch FLOW programme on Far and Large Offshore Wind energy were officially presented to Minister Henk Kamp of Economic Affairs during the Dutch Wind Days. Perhaps the most important takeaway from the FLOW book is that cooperation between industry, knowledge institutes and government can achieve considerable cost reductions in offshore wind.

In fact, cost reductions are already happening, as was shown when Kamp revealed, at the end of May, that bid prices for two offshore wind energy concessions off the coast of Zeeland, 760 MW in total, came in “considerably lower” than the maximum price that had been set at 12.4 cts/kWh. He did not say how much lower – this will be revealed in mid-August – but they were “lower than expected”.

“What would happen to our business if policy makers decide to abolish the subsidies? The best way to counteract that uncertainty is to become subsidy-independent”

This was exactly the signal that the offshore wind energy industry in the Netherlands wanted to convey, and that authorities wanted to receive. It is the result of consistent efforts at cost reduction that have been made in the Dutch offshore wind sector, at least since 2010 when the FLOW programme was started. In 2013, when the Dutch government, energy industry and NGO’s signed an “Agreement for Sustainable Growth”, a goal of 4450 MW of offshore wind capacity was set for 2023, with the condition that offshore wind farms would need to produce at 40% lower costs in 2024 compared to 2014. The Dutch subsidy programme has been largely adapted to that cost curve.

This cost reduction will not yet get offshore wind power to a competitive level with fossil fuels within the current market conditions (which do not include societal cost), but it would be a giant step. Moreover, if the same cost reduction pace is sustained, a competitive level could be reached between 2025 and 2030.

Strategic activity

The 40% cost reduction target originated from FLOW, a five-year R&D programme in which industry, research institutions and utilities participated. The participants set themselves this target because they realised that offshore wind could only grow significantly if costs are drastically cut. As one of the FLOW participants from industry said: “Offshore wind is a strategic activity for our company. But what would happen to our business if policy makers decide to abolish the subsidies? The best way to counteract that uncertainty is to become subsidy-independent.”

The strong input of business is an important characteristic of the FLOW consortium. Companies that were heavily involved in FLOW include the following:

- Maritime constructors like Van Oord and Ballast Nedam, by 2005-2010 already quite well positioned in offshore wind construction, wanted to preserve and increase their business in a sector that promises to double or triple in the next ten years.

- Utilities identified offshore wind as the main component in renewable energy in the Netherlands within the next decades.

- TSOs took up the challenge to develop offshore solutions for connections to the grid.

- Turbine manufacturers: entrepreneurs identified opportunities to develop new offshore turbines almost from scratch.

- Service suppliers and consultants recognised the potential for using new techniques in highly complicated turbine systems.

Small improvements

The FLOW cost models show that cost reduction in offshore wind energy is the result of a large number of relatively small improvements, often contributing just 1 to 2% of the total. The individual cost reductions cannot simply be added up, because they are often interrelated. For instance, an improved operation control that would individually contribute 2% of cost reduction cannot simply be added to a 5% rotor improvement resulting in a 7% improvement. Neither can you apply a new type of monopile (on which the turbine is built) and a new type of foundation at the same time.

“Parties which worked in the same field but never talked to each other, now work together. This has placed offshore wind high on the Dutch political agenda”

Some improvements have more potential than this typical 1 or 2% reduction. That applies for example to the turbine itself. The increasing size of turbines on the international market, presently reaching 8 MW. and even more importantly, larger rotors, up to 80 metres in length, is responsible for up to roughly 10% of the cost decrease over five years. The foundation and the design of a wind farm can also contribute substantially, up to roughly 5%. In addition, financing is an important factor. Low interest rates (such as we have now), but also increased confidence and a low risk premium, can reduce costs by up to 5% or more.

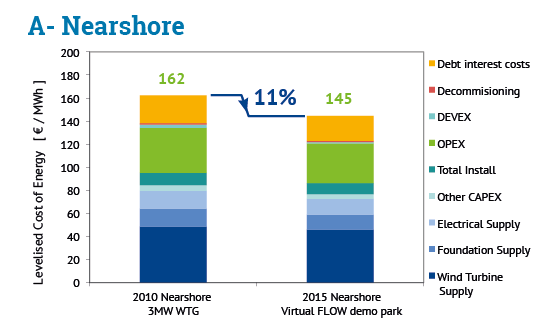

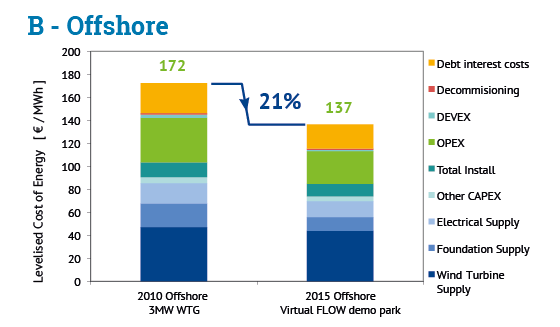

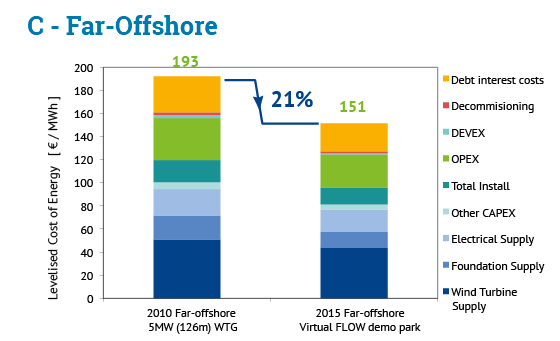

A summary of cost reductions for nearshore, offshore and far offshore wind turbines in five years of FLOW

Cooperation

One of the most important conclusions that can be drawn from the FLOW programme is that achieving the cuts through innovations needs quite an extensive and sustained R&D effort. What counts even more is cooperation and information exchange within the sector. R&D needs input from industry and vice versa. Government too is an important partner in the process, to deliver long term market stability, R&D funds and efficient permitting and project tender procedures.

As RWE’s CEO Peter Terium, chairman of the FLOW board, concluded “The cooperation at CEO level is special. Parties which worked in the same field but never talked to each other, now work together. This has placed offshore wind high on the Dutch political agenda.”

FLOW, exemplary R&D in the Netherlands

FLOW has been a good example of how cooperation in the sector should look like. CEOs of companies that normally compete (utilities, manufacturers, supplies) have been involved from the first moment, putting their common interest in accelerating offshore wind energy business above their individual market position. That has nothing to do with altruism, but it’s a simple calculation: when the market grows, business grows. At this stage of the technological S-curve, this attitude proved to be very fruitful. The example of demand driven research in the Netherlands is now broadly applied in the Topsector policy.

How to prevent pitfalls?

The level of Dutch knowledge about wind energy development has been promising before. Also in the eighties and nineties of last century, Dutch knowledge was top ranked in global (onshore) wind energy. And although important players in the supply chain exist like LM, SKF, VDL Klima, Mecal, nowadays there are no top ranked wind turbine manufacturers in the Netherlands.

The the perspective for the Dutch economy for offshore wind energy is quite different now. Maritime constructors like Van Oord, Volker Stevin and Boskalis are already world famous for offshore construction, also in wind energy. Tool developers for offshore and ship building for special challenges are also well positioned, e.g. Royal IHC. Harbours and shipping are a sound foundation for multi-gigawatt offshore wind activities on the North Sea. Regarding manufacturing, two newcomers are trying to establish their offshore wind turbine business: XEMC Darwind (owned by Chinese XEMC) and 2-B Energy. And last but not least: Dutch policy ambitions are high.

However, FLOW also shows the pitfalls. Developing an industry on a young technology is not exactly self-propelling. It needs a coordinated approach, in which developing a home market is seen as the most important, by many of the FLOW-participants. The ingredients are there, but now that FLOW ended, there is no room for leaning back. The FLOW approach was fit for the last five years, and is probably not exactly fit anymore for the coming years. But putting up a national business requires at least some of the important FLOW agreements: cooperation where needed, competition where timely, and deep commitment of national authorities and business CEOs that offshore wind has the future.

Rolf de Vos is journalist and author of “The FLOW book: Competitive through cooperation”, which was presented to the Dutch Minister of Economics Henk Kamp on 15 June at the Wind Days in Rotterdam.

Ernst van Zuijlen is programme director FLOW and TKI WOZ (Top knowledge Consortium on Wind at Sea).

Share this page

Share this page